Newsletter Answers

November

Dr. Sarah E. Bortz Case Challenge Answers

Answers:

e e

Discussion:

The patient diagnosis is presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, (POHS). Although endemic to the Ohio-Mississippi River Valley region where 2% of individuals in that region exhibit peripheral atrophic scars, "histo spots", this diagnosis should be a differential for any patient with two of the three, 1. peripheral atrophic scarring, 2. peripapillary atrophy or 3. choroidal neovascular membrane

POHS is caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Histoplasma capsulatum is found in bird droppings such as chickens, pigeons and blackbirds. It is contracted through inhalation where the dimorphic fungus passes to the choroid through the bloodstream. It is termed presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, because diagnosis is based on ocular findings and there are no confirmatory studies to implicate the fungus. Ocular findings include peripapillary atrophy, "punched-out" chorioretinal lesions, absence of overlying vitreous involvement and sometimes, choroidal neovascular membrane, (CNVM). CNVM causes a decrease in vision that is often the presenting symptom. The cause of the CNVM is not clear, but it is thought that areas of focal inflammation within the retina cause a disruption in Bruch's membrane therefore predisposing the eye to CNVM formation.

The treatment and management for POHS depends on the status of the disease. A patient with only peripheral atrophic scarring and peripapillary atrophy will require monitoring annually, whereas a patient with atrophic scarring in or around the macula might require more frequent monitoring in the office as well as monitoring at home with an Amsler grid. Once a CNVM has formed causing a change in vision, treatment is necessary. Treatment options include focal laser photocoagulation, PDT, surgical removal, or as in the case this patients' case, intravitreal anti-VEGF. After one injection of Avastin, this patient experienced a two line improvement in vision and was instructed to return in two months.

Dr. Kelly Cyr Case Challenge Answers

Answers:

c Trauma c Topical Prednisolone Acetate QID d All of the above

Discussion:

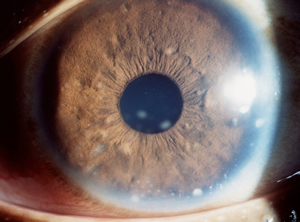

Iridocyclitis is a type of uveitis concerning inflammation of the iris and ciliary body. It involves the presence of white cells in the anterior chamber and the retrolental vitreous. Patients are usually symptomatic for pain, redness, photophobia and sometimes decreased vision. The onset, duration, severity and laterality (unilateral or bilateral) of the condition should be determined. In addition, clues to diagnosis can be obtained through assessing patient's age, race, ocular history and review of symptoms.

On examination, different features can help distinguish between granulomatous vs. non-granulomatous disease. The type of keratic precipitates (if present) should be evaluated - fine KPs are most often present in non-granulomatous disease and "mutton-fat" KPs are associated with granulomatous disease. The iris can also provide clues. Posterior synechiae are usually indicative of a more chronic problem and the presence of nodules (either Busacca or Koeppe nodules) can indicate granulomatous inflammation.

The most common etiology of unilateral acute-onset anterior uveitis is human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27-associated disease. Patients with alternating or recurrent unilateral episodes of uveitis should be screened for HLA-B27 and asked questions to rule out HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter Syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis, etc.).

In cases of iridocyclitis that are bilateral, severe, recurrent or granulomatous a work-up should be performed to rule-out systemic disease. At minimum, the following tests should be ordered: complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), reactive plasma reagin (RPR) and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, purified protein derivative (PPD), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS). A Lyme titer may be considered in endemic areas and a chest x-ray may be ordered in those presenting with symptoms of sarcoidosis.

In the case presented, the above work-up was performed since the patient had bilateral disease and the inflammation in the right eye appeared more chronic. Upon questioning, the patient reported a history of syphilis about thirty years prior. All tests ordered were negative except for the VDRL and RPR. Note that VDRL testing will be positive in patients with either inactive or active disease; however, RPR testing is only positive in patients with active disease (RPR is usually used to detect response to treatment). The patient was started on homatropine twice daily in both eyes and prednisolone acetate 1% four times daily in both eyes. He was referred to his primary care doctor for necessary treatment and recommended HIV screening.

Syphilis can manifest in almost any part of the eye and may occur at any stage of the disease. Uveitis is the most common presentation of syphilis. It may be the only presenting sign or may occur many years following initial infection during the late stage of syphilis. Ocular inflammation can be either granulomatous or non-granulomatous and can involve the anterior or posterior segment or both. Today, with the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, syphilis comprises only about 1-2% of all uveitis cases.

In addition to treating the ocular inflammation associated with syphilis with topical corticosteroids and a mydriatic, penicillin G is the preferred drug for treatment at all stages. Sexual partners should also be tested and treated when necessary.

Dr. Kelly Cyr Opto-Geek Trivia Answers

Answers:

d Facial nerve (CNVII) b False e All of the above should be included in the differential for facial paralysis b False b Surgical decompression of CNVII

Discussion:

The facial nerve is a mixed nerve consisting of both motor and sensory fibers. The facial nerve is responsible for tearing, salivation, taste (anterior two-thirds of the tongue), and controlling the muscles of facial expression. Paralysis of the facial nerve results in the inability to raise the eyebrow, difficulty closing the eye, and drooping of the corner of the mouth. Patients may also experience decreased taste sensation, hyperacusis or dysacusis, or a decrease in salivary or lacrimal gland production.

Differential Diagnosis

Facial nerve paralysis may result from a number of different etiologies - ischemic, infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, traumatic, or neoplastic. One should consider identifiable causes of facial paralysis prior to labeling the palsy as idiopathic or a "Bell's palsy".

Bell's palsy accounts for over half of all cases of facial nerve paralysis. It is a unilateral, idiopathic peripheral facial paralysis caused by inflammation of the facial nerve. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and usually presents acutely and develops within hours to a few days. Resolution of Bell's palsy usually occurs over three weeks to three months.

Non-idiopathic facial nerve paralysis tends to have features that are distinguishable from Bell's palsy. The patient may have weakness to other areas of the body or various other symptoms. The onset of the palsy tends to be more gradual and may or may not be associated with a prodome of twitching of the facial musculature. It is important to recognize and treat potentially life-threatening causes of facial nerve paralysis. One role of the optometrist should be to ask the patient questions to rule-out other causes of facial paralysis including (but not limited to) the following: a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), Ramsey-Hunt syndrome (caused by Herpes Zoster virus and involving vesicles on or within the ear), Lyme disease (especially those living in endemic areas), otitis media (especially in children), sarcoidosis, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, Guillan-Barré syndrome, trauma or neoplasm (acoustic neuroma, facial nerve schwannoma, tumor of parotid gland or perineural spread of a skin tumor).

Evaluation of facial nerve paralysis

In the evaluation of a facial paralysis, a case history is extremely important in eliminating many of the possible etiologies. Patients should be questioned on the following: recent trauma? recent surgery? recent vaccinations? summer-time camping or hiking in the woods? twitch or spasm preceding the onset of paralysis?

In examining the patient, an astute clinician should look for the following: vesicles or scarring around the external ear? lesion or inflammation of the parotid gland? other cranial nerve involvement? loss of hearing? rash or facial edema? In addition, the presence of a Bell's phenomenon should be assessed as those with a poor Bell's phenomenon have more risk of corneal exposure and desiccation.

Lab testing should be ordered to rule out suspected etiologies. Appropriate lab tests may include a complete blood cell count with differential, serum glucose levels, Lyme antibody titers, angiotensin converting enzyme, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies and cerebrospinal fluid analysis for cytomegalovirus, rubella, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis A, B or C, or varicella zoster virus. Imaging studies may also be performed in those with atypical presentations, multiple cranial nerve involvement or minimal improvement in the palsy over six months.

Treatment

Treatment of facial paralysis is aimed at providing corneal protection through the use of excessive lubrication, moisture goggles, temporary tarsorraphy or taping of the eyelid closed. If necessary, in cases with an identifiable diagnosis, the cause of the facial paralysis should be treated.

Treatments for aberrant regeneration, poor cosmesis, or chronic exposure of the cornea due to incomplete recovery are longstanding considerations. Surgical decompression of the facial nerve has been attempted in the past but is not currently recommended as a standard treatment due to risks including deafness, seizures, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid and facial nerve injury.

Botulinum toxin injections (Botox ®) from the bacterium Clostridium botulinum is another mode of treatment and is usually employed later to reduce facial spasm or synkinesis. Botox injections last about three to six months; therefore, patients should know that the effect is not permanent.

In persistent paralysis, gold weight insertion into the upper eyelid may be performed. This is the most common surgery following facial paralysis and involves a small gold weight inserted into the upper lid to assist in eye closure or improve the blink.

Further, patients should be guided in the direction for psychological support as facial disconfiguration can have a significant impact on a patient's quality of life.

August

Multiple Choice Answers

c b d

Discussion:

This patient has phlyctenulosis, a condition that is sometimes bilateral, self-limiting and most often occurs in females in their first or second decade of life. A phlyctenule typically appears as a wedge-shaped nodular lesion with engorged hyperemic vessels that is near the limbus on the bulbar conjunctiva and/or cornea. Patients can report a multitude of symptoms including photophobia, foreign body sensation, lacrimation and redness. The mechanism of phlyctenule development is not completely understood, but is thought to be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. In developed countries it is often caused by hypersensitivity to staphylococcal cell wall antigen, but can also be caused by hypersensitivity to tuberculin protein, Coccidioides immitis, (a soil based fungus common in the Southwest), chlamydia, intestinal parasites, Candida albicans, among others. If you are suspicious that tuberculosis may be the cause, it is prudent to order a PPD and chest x-ray.

The differential diagnoses for phlyctenulosis are pingueculitits, episcleritis, sterile or infectious infiltrates and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Treatment for phlyctenulosis most often involves a combination of steroids and antibiotics. A general recommendation would be topical corticosteroids used every 2-4 hours with an antibiotic ointment at bedtime. It is important to maintain treatment as long as symptoms persist with weekly follow-ups. Once an improvement is noted, begin a steroid taper, maintaining the use of antibiotics until the steroid is finished.

In many cases, phlyctenulosis is associated with blepharitis. For this reason, patient education on eyelid hygiene to be continued indefinitely is essential. The most common systemic association of phlyectenulosis is rosacea. If you suspect rosacea to be a contributing factor, adding an oral regimen of doxycycline 100mg QD-BID for 2-4 weeks can speed recovery and prevent progression. You might consider prescribing metronidazole TID, a topical gel used to treat inflammatory lesions of rosacea.

Although self-limiting over a period of 2-3 weeks, phlyctenulosis can become severe and cause thinning of the cornea and perforation. Even as a mild form it can cause patient discomfort, a decrease in vision, issues with cosmesis and in the case of this patient contact lens intolerance. Phlyctenulosis may also be the indication of a severe underlying systemic pathology such as tuberculosis and although the CDC reports a decline in reported cases of tuberculosis from 2008-2009 in the United States, it is still the leading killer of those who are HIV infected

February

Opto-Geek Trivia

Anterior Uveitis

b e b a a

Busacca nodules on the iris surface and a few mutton-fat keratic precipitates on the inferior aspect. |